All My Love, Alex: Second Prize Winner EVENT Literary Magazine

I’m delighted to announce that my 5000-word essay All My Love, Alex received second prize in the 2021 Event Poetry & Prose Magazine Creative Non-Fiction contest. Award-winning Canadian poet and writer, Lorna Crozier, called Event Magazine, “Simply one of the finest literary magazines in the country,” so I am beyond honoured to find my work published there and in the fine, fine company of first-prize winner Cayenne Bradley and third-prize winner Nicole Boyce. The literary competition was judged by DAVID A. ROBERTSON, the 2021 recipient of the Writers’ Union of Canada Freedom to Read Award. He is the author of numerous books for young readers, including When We Were Alone, which won the 2017 Governor General’s Literary Award and the McNally Robinson Best Book for Young People Award (as did his acclaimed YA series, The Reckoner). His award-winning memoir, Black Water: Family, Legacy, and Blood Memory, was a Globe and Mail and Quill & Quire book of the year in 2020. He is also the writer and host of the podcast Kíwew. He is a member of Norway House Cree Nation and currently lives in Winnipeg.

Here is what Robertson had to say about All My Love, Alex.

‘Thinking of the things you might have done.’

We try to make sense of the past because if we can make sense of what has happened, we can better comprehend where and who we are. At the same time, we manufacture our lives and the lives of those that came before us because there’s no other option. Our memories are comic-book panels, and we exist within the gutters, doing our best to connect images to find meaning. All My Love, Alex, by Vicki McLeod, the second-place winner, articulates this truth with polished prose and an impressively innovative approach to storytelling, creating a ‘collage of writing’ that brings us along on the writer’s path to understanding. I loved the blend of historical records, found poetry and personal essays to create a portrait of a man who has left the writer behind, as well as a man who has discovered an intimate sense of identity.‘

This essay is part of a larger body of work where I am attempting to carve out the story of my father in order to find meaning in my own story. The collage form that Robertson references in his remarks is the one that I find best expresses the way memories emerge and piece themselves together as we unfold the narrative of our lives. I used a similar technique in a shorter braided essay on the same subject that was also listed for a literary prize. You can read about that piece here.

This material is tender territory. I am writing about the real lives of others, and my own life as well. Memory can be treacherous, remembering can be painful and triggering. I am working with glimpses and fragments. Always, I treat my writing self with love and patience and I am grateful to the sensitive skill and experience of my writing teachers– poet Rob Taylor and author Christina Myers– for their support as I develop this work. My dear friends (and Secret Poets Club), Faye Luxemburg-Hyam and Seija Juoksu listened to early drafts, and held my breaking heart with gentleness. Debra Dunsmore offers unwavering and ongoing encouragement for all my writing and creative work, and always, always asks about my work. Thank you! I owe a special debt of gratitude to Ali Davies for holding me to loving accountability in alignment with the highest coaching principles and in the spirit of friendship.

When being immersed in the past overwhelms, I take to the sea. There, standing on the shore I find Victoria Pawlowski, Brenda Moffat, and Kristy Williams, wild swimmers who willingly wade into the deep water with me. Joseph Kakwinokanasum, Ann Wilson, and Marion Dodds, of my 2018 SFU Writers Studio cohort, are always only a text away. My thanks to all of you for always standing where you can be seen. It means more than you know.

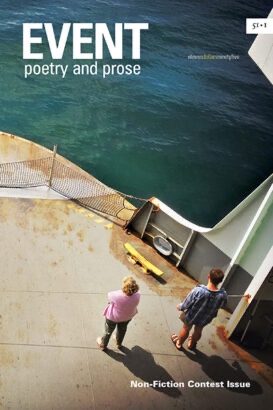

https://www.eventmagazine.ca/shop/product/current-issue/event-511/

From the introduction to the prize-winning piece:

“In 1961 my mother committed my father to Crease Clinic, at what was then known as Essondale, the Hospital for the Mind. This was a euphemistic title for what is usually called a mental institution or lunatic asylum. Later, this asylum became more widely known as Riverview. I first heard of his breakdown and subsequent institutionalization in 1978 when my mother showed me the letters my father had written to her from there. I was 18 and we had not lived with my father for many years. The letters were folded into a frayed glossy turquoise and pink greeting card with a still life of carnations and red roses on the cover. Old-fashioned, even for the time. Printed out in delicate white script: A Birthday Message for My Wife. The bundle was wrapped in a red satin ribbon. I read the letters, and at the time they didn’t make much of an impression on me. I was in a kind of shock, trying to make sense of this new information, searching my memory banks for even a glimmer of awareness about this period of my parents’ lives. At the time of my father’s institutionalization in 1961, I was three years old. My baby brother not quite 1. My mother, who signed the committal papers, just 21. My father, 25.

The bundle of letters languished in a cardboard box of keepsakes for many years, and in the COVID winter of 2020 I reread them. I began to see in the sloped lines of my father’s handwriting a glimpse of the story behind his mental illness and alcoholism. I requested and received his treatment records from the British Columbia Royal Museum Archives. By the time I entered recovery myself in 1988, my father had been dead for four years. He was institutionalized for a propensity toward depression, schizoid personality and suicidal thoughts. Using a combination of personal essays, verbatim treatment records and found poetry based on letters, this collage of writing maps a journey toward understanding.

My father signed his letters All My Love, Alex.”

You can find the complete essay here.